I have a love/hate relationship with outreach events. I love them because most of my work is public-facing but done behind a curtain, so getting direct feedback from the people using my work is always nice. I hate them because you have to be on your tiptoes for hours on end, never knowing what’s next and if anything is about to go catastrophically wrong – or right!

There have been several such moments during Science4All 2023, where I was exhibiting my little corner of “boring video games” with the rest of my lab. Three things stuck with me.

- That guy that glanced at the title screen of “Cash or Card?“, went «I’ve already had a shop and it’s already failed,» and ran away. OK buddy. Sorry your shop failed. Not my fault. Had I been quicker, I’d have asked him to take my survey anyway.

- That kid who sat down to play and proudly declared «I’m going to have everyone pay by cash so that the bank doesn’t steal all my money!» At the end of they day he went to deposit his hard-earned cash into the bank «so I lower my risk of robbery.» I then proceeded to point out that his bank deposit wasn’t free and that the bank took a fee, and his face dropped as he was babbling something along the lines of «but… but… but… I thought…» Suffice to say he drastically changed his strategy and went on to victory!

- Kids in the age rage of about 8 to 13 were fiercely more passionate about the game than their 13-19 peers, and way more than other adults. It is true that this particular event is mainly done for kids, so any chance they get to be hands-on, they’ll take it. But I was still a bit taken aback by the enthusiasm! At this point I’m not even sure that “they’ll play anything that looks like a game” is not true!

A few considerations are in order. On the kid from point 2, I wouldn’t be surprised if at least one of his parents or relatives owned a shop or had to otherwise handle payments, and exposed him to a way too common anti-electronic-payments rhetoric which he sucked up like a sponge and parroted back with limited understanding. Kids are definitely not stupid, but neither they are the most proficient critical thinkers when it comes to information descended from a figure they perceive as authoritative even if it is not. Which is sadly not too different from what happens with adults anyway, and a very good reason for more research on educational video games. More on this later.

Still on point 2, the cash deposit fees in the game are computed more or less randomly based on limited data I found online and from my personal experience. Many banks have cash deposit fees if you go to a human teller, but some also have ATMs that handle cash deposits, typically for free, so applying a random fee to all the deposits in the game is not necessarily realistic. However, if you consider a mix of non-zero fees and account fees, the approximation of a fee randomly chosen between 2 and 4% is more or less realistic at the end of the year. All in all, in Italy it’s still very hard to find a basic bank account that costs nothing. If you are lucky, you can zero the costs if you meet certain conditions – like, pay in a certain amount, and have a certain number of direct debits per month – and despite this the bank is still required to pay a small annual tax which they’ll be damned if they don’t pass it on to their customers.

“Better” video games

One adult I had a pleasant chat with stated the obvious: «they already play video games a lot, and taking them away is useless and counter-productive, so might as well make better video games, right?» Yes, you are right. This adult was impressed with the fact that someone was doing this kind of work, but wasn’t entirely impressed with “Cash or Card?” – although they were quite impressed with their kids interest in the game, which frankly flabbergasted us both.

It’s conversations like these, and countless others I’ve had, both on- and offline, that remind me of the importance of doing this kind of work – and doing it in the rigorous framework of academic research. Yet, the sad truth that emerged during the Science4All day is that video games still carry a lot of stigma in 2023 – although fortunately the times, they are a-changin’. One could chalk this up to people not being up to speed with the latest trends, the latest research, and the marvelous world of indie games. But let’s be honest: if all they have is their outsider’s perspective of seeing kids spending hours on the latest trendy first-person shooter, or on the most frivolous aspects of Minecraft, it’s hard for them to imagine that the medium can give them more than a few hours of mindless distraction. And it’s even harder for adults to imagine their role as video game players instead of confused spectators, and to imagine what they can gain from playing video games.

Going forward

I come to this point one month from the end of my first of two years of funding on this project, so I feel like I have to evaluate where I am and where I am going from here – and what are the chances of grabbing more funding, or having to find a “real” job in a year’s time 🙂

The plan has changed quite a bit from what I proposed in my original MSCA application, and that’s fine. If we knew everything in advance, the work we do wouldn’t be as interesting and challenging. At this point, I was planning on having a game out, experimental data collected, a paper out, and be working on the next iteration. Save for the experimental data – more on that later – I have a game out and I have a paper out, which is great news. It’s just that the game was not developed in the way I hoped for within this project, and the paper is a good paper but not about the game.

However, as one attendee to the GoodIT conference said, «and what are you teaching us? That educational games suck?» so which I replied «yes» with all the gravitas I could impart to it on the implication that sometimes, in research, we have to the obvious because no-one had done it yet. I’m not sure I conveyed the message, but I made sure to let them know that a game prototype was coming out shortly.

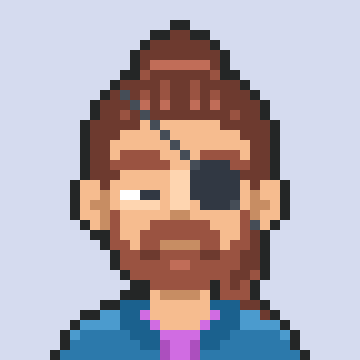

Going forward: The Next Iteration

And as far as the next iteration, that plan has changed a bit too. I have a proof of concept, but I haven’t worked with educators nor game designers on it, which is kind-of the whole point of this project. To be perfectly honest, “Cash or Card?” started out as my own frustration vent about the insistence of some shop keepers of demanding cash payments despite the law in Italy saying they have to accept electronic payments too. The subject is complex and it’s not worth going into here. By the start of summer, I had enough of people claiming that the fees were too much or that the card machine was broken or offline, so I decided to run a simulation to see how bad it was. Spoiler: it wasn’t. Considering that it is possible these days to take out contracts with very low fees – bordering on zero, sometimes – I just went ahead and made the game. I gathered a roughly realistic estimate of the costs, and turned my simulation into a “Papers, Please” inspired game.

In all this, I had to wear three hats: the domain expert, in gathering the fundamentals to make the game feel plausible; the game designer, in making the game challenging and engaging enough – I’m not sure I achieved that but hey; and the researcher, in collecting behavioral data and feedback from the players. Being a technologist and a researcher, I think I did an OK job, but the game could have turned out better. It definitely feels like a lecture, and doesn’t have very much of a replay value – although early feedback from Science4All attendees was mildly encouraging.

Going forward: The Struggle

I keep saying to anyone who listens that the next step in the project will be gathering educators and taking their perspective, expertise, hopes, and wishes, and the step after that would be to involve game designers, sit everyone in the same room, and produce at least one game at least vaguely related to the theme of disinformation. I have already started reaching out to educators and I got some decent feedback, but I am struggling to get and sustain enough attention and momentum – and with educators, they’ve got plenty other things to do and a hard enough job without having to work with me! 😬

The other issue is that there are very few and very small incentives to make educational video games. There isn’t enough money to entice game developers, and there isn’t enough expertise to turn educational content into good games. I often hear that «educational video games are sold to parents and teachers, not to players» and that would be the reason for why these games suck. I’ve never played any of the titles by Humongous Entertainment, but I hear they were very much appreciated by players, so there must be ways of making games that don’t suck – I just don’t know what they are, and I’ll never repeat this enough: I need the help of game designers and educators to figure it out.

Going forward: The Call To Action

Get in touch!

- If you are an educator, not necessarily a school teacher, and/or a domain expert, and especially if you already use video games as part of your work, I want to know how you use them, what games you use, and how they benefit your work. I want to know what you wish educational video games would be like and what they could teach, and I want to help you make your dream edugame. But most importantly: let’s have a chat!

- If you are a (video) game designer, I promise there is a lot you can get from this project, and a lot you can contribute! I want to make educational video games for players, not for their parents or teachers! Actually, I also want to make them for their parents, their teachers, and their grandparents too – but as players, not as parents, teachers, or grandparents. Disinformation is something we are all exposed to, and we are even more at risk of falling victim to it once we leave school and hit the road, so finding ways of incorporating bits of “vaccine” into everyday life is a great way of promoting lifelong learning, and that requires replayability and continual engagement. I’m sure you know something about these, right?

- If you are a (video) game researcher, I want to learn how you evaluate educational video games, their efficacy, their entertainment value, and everything there is to learn to make sure we don’t just let new games fall flat on their bellies. Educators and game designers want to get feedback after they pour their precious time and expertise into a project, and we are uniquely placed to help with that.

I want us all to sit in the same room – or in the same conference call at least! – and bring out our best ideas to create, use, and evaluate “better” educational video games. I want us to learn things from each others, and I want us to distill what we learn in practice, development, and evaluation guidelines to help us make more, and “better,” educational video games. Whatever “better” means.

If you are interested, you’ll find more information here, or get in touch! 🙂

Bonus track – or how things can go catastrophically wrong

And now for some light entertainment and lessons harshly learned!

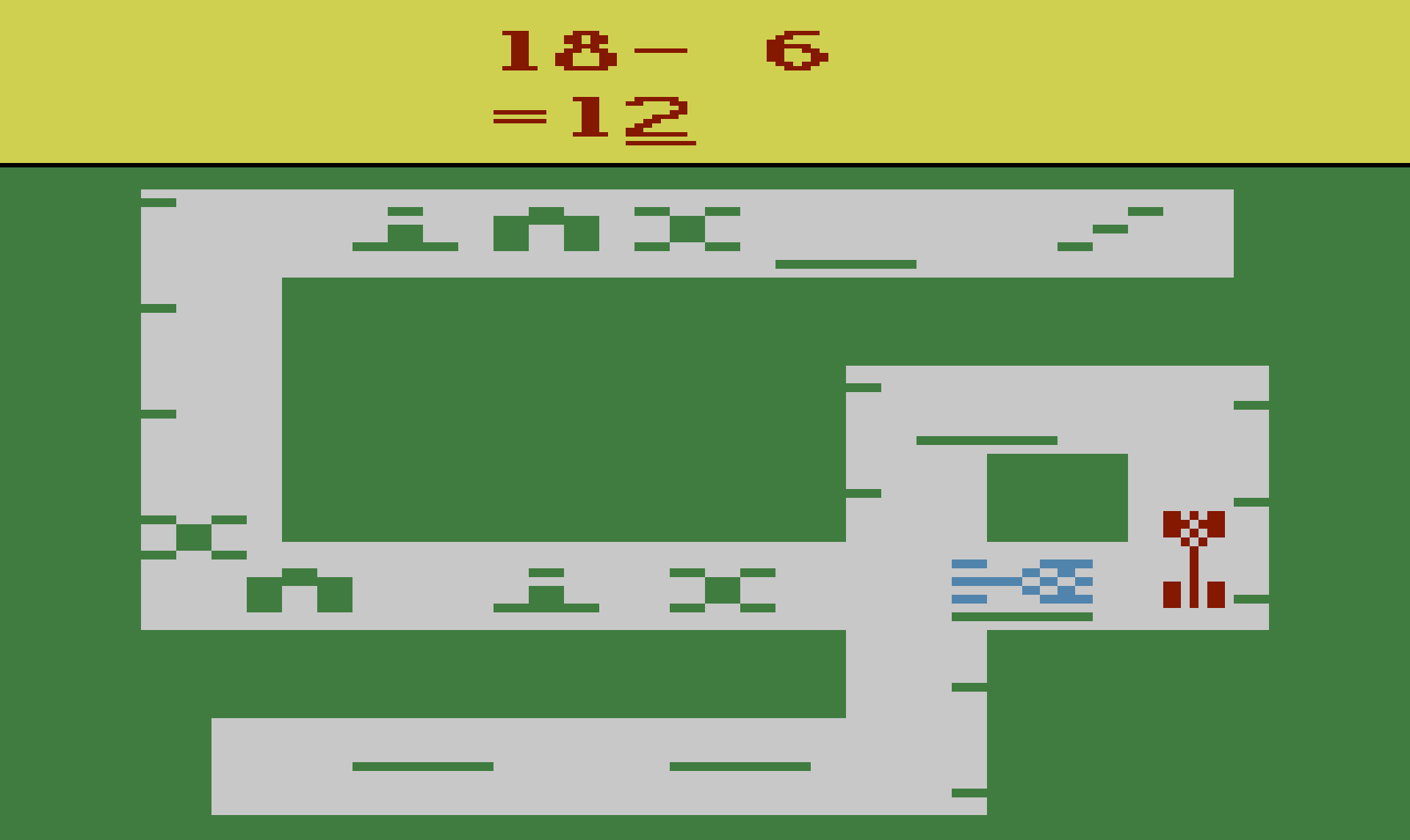

If you went through the source code for “Cash or Card?” you might have noticed some amount of data collection. Just to be clear, no personally identifying information (PII) is collected at all, just action logs of pretty much everything that happens during a game along with an anonymous ID to tie a game together. I set the game up to log events to a CouchDB server I host on my VPS – the same VPS on which this web site is hosted – so I know that the data aren’t leaving my control. And I also set up a very simple visit counter with Matomo – also hosted on my server, just in case.

The problem is that I tested everything thoroughly running the project from the Godot editor, but never thought of testing it while deployed online. I chose to deploy the game online so I could have people scan a QR code and bring the game home on their phones, and the idea worked fairly well as far as I could see with my own eyes.

As far as I can see through the logs: no idea. Having misconfigured my CORS headers, the logging code wasn’t able to connect to the CouchDB server because it technically resided on another domain, and so I pretty much lost all the game data from the day. And as far as Matomo goes, it turns out that uBlock Origin is far better than I thought at blocking trackers and so I should at least have disabled it from the browsers I was using on location.

So, I have absolutely no idea how many people played my game on its launch day 😰 No, actually I have a few hints thanks to good old server access logs, but those are hard to parse.

Oh, well.